NaNoWriMo Underway

November 2, 2010

I’m a rebel. I’m doing what I want, and ignoring the rules. Usually I’m the goody-two-shoes perfectionist, but as far as writing a manuscript was going, that wasn’t working for me.

I’m a rebel. I’m doing what I want, and ignoring the rules. Usually I’m the goody-two-shoes perfectionist, but as far as writing a manuscript was going, that wasn’t working for me.

I readily confess that I can’t remember how I ever wrote a book in the first place. Somehow I did, but as I’ve thought about writing a second manuscript, I kept returning to the feeling that it was a fluke. I didn’t feel I’d ever be able to do it again. Even restoring the mysteriously deleted companion website felt beyond me.

Then NaNoWriMo came along. November is National Novel Writing Month. This is the twelfth year of the event that encourages writers of all ages to write a 50,000-word piece of fiction by midnight November 30.

I’ve known about NaNoWriMo for several years, but never considered trying it. Just don’t feel like I have a plot in me, though I’d love to be a novelist or poet. Inspired by the special deal on Scrivener for NaNoWriMo participants though, I looked around a bit more yesterday, and I found that the rules are really a good bit looser. You can be a rebel and write nonfiction if you want. The goal is just 50,000 words of whatever. As the seed post on the Rebel forum explains, “This is a self-challenge. The REAL prize of NaNoWriMo is the accomplishment, and the big new manuscript you have at the end. Everything beyond that is icing on the cake.”

So I decided to set up a profile and try to crank out a book draft. Not sure that I will make 50,000 extra words since I have many other things I need to write this month. Still I can try. After midnight on November 1, I created a working outline, based on revisiting my first book, Designing Writing Assignments. Scrivener made this so easy. I created a bunch of folders and tucked some text inside the jotted out what I was thinking of putting there. Done.

In the wee hours of today, November 2, I collected notes and ideas from a few places to copy & paste some very rough ideas into place. That’s where the cheating part comes in. Technically, people write all new text for NaNoWriMo. For my purposes, that’s a silly restriction. I reread sections of Designing Writing Assignments last night, probably for the first time in more than a year. I realized how much of the book had been culled from things that I’d written elsewhere.

That artificially inflates my word count, I know. The thing is that I know I’ll edit it back down as I make all that pasted stuff fit in properly. Even though I know my draft is nothing but a collection of jottings and pastings, it feels remarkable to have collected 12,263 words of stuff. I can actually believe book in my head.

It’s only been two days, but so far NaNo has helped me remember how to write a longer work. And I’ve been freewriting like a fiend—I have the most typo-filled mess ever, but I typed things down. I gave my permission not to be to clean and neat. I just want to gather a bunch of text. I can edit later. If I do nothing else, I’ve accomplished a great deal.

This prompt is inspired by the piece that I

This prompt is inspired by the piece that I

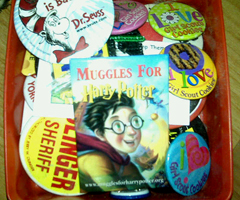

One of my cherished possessions is a Muggles for Harry Potter pin from 1999. Eric Crump gave it to me, having picked it up from the NCTE librarian. I hadn’t read a word of J. K. Rowling’s first book, but I was willing to join the anti-censorship campaign.

One of my cherished possessions is a Muggles for Harry Potter pin from 1999. Eric Crump gave it to me, having picked it up from the NCTE librarian. I hadn’t read a word of J. K. Rowling’s first book, but I was willing to join the anti-censorship campaign.