Which Books Would You Ban?

July 15, 2011

What do Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, and Ann Coulter have in common? How do they differ from Adolf Hitler, Ayn Rand, Michael Moore, Andrew Breitbart, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Michael Savage? A Rebel Pundit survey last month asked, “Which of these books would you be interested in having banned, if you could have books banned?”

What do Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, and Ann Coulter have in common? How do they differ from Adolf Hitler, Ayn Rand, Michael Moore, Andrew Breitbart, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Michael Savage? A Rebel Pundit survey last month asked, “Which of these books would you be interested in having banned, if you could have books banned?”

The results were overwhelmingly in favor of banning the books of Palin, Beck and Coulter, though the math of the survey is a little confusing since the results don’t add up to 100%. That said, what’s going on here?

Rebel Pundit’s reporter set up on the street in Chicago, during the Printers Row Literary Festival. As these alleged book lovers passed by the reporter, he asked them which books they’d like banned, telling them they could ban up to three, and handing them a Sharpie so they could make tick marks under their choices. Before I go on, watch the Rebel Pundit video of folks participating in the survey:

Sadly, people take the marker and willingly step up to the poster. The editing of the video suggests the participants aren’t really thinking much. They don’t even interact much with the reporter, other than taking the Sharpie from his hand.

In fairness, Rebel Pundit does explain that there were naysayers:

Nine people explicitly stated to us they thought banning books was wrong, including two individuals who voted on the board but later approached us to say, (paraphrasing) “I think I made a mistake, and wanted to take my votes back if I could, because after further reflection, I think banning any book is wrong.”

Only nine people of 147 protested the idea of banning books. Of course, the point of the survey isn’t really book banning. It’s to demonstrate that people make choices without thinking.

My hunch is that the reporter expected people to vote unthinkingly. Rebel Pundit is a conservative blog. According to their About page, they are “a beacon of truth, showing the unholy alliance of the local mainstream media and the progressive Democratic Party.” Since Chicago is a traditionally liberal town, the video and related article depict the people of Chicago as foolish lemmings:

While there were in fact less than two handfuls of individuals who did tell us they don’t think any books should be banned, unfortunately there were a shocking amount of guests at this book fair who were quite open to the idea, and in fact lined up quite excited for the opportunity to voice their opinion.

Given the audience of the Rebel Pundit site, the site likely guessed that their readers would draw the connections that the liberal democrats at the book festival were actually interested in limiting individual freedoms by stepping up happily to ban books. You don’t need to read many of the comments to see that it worked.

How to Use the Video in the Classroom

Because of the way that people blindly choose to ban books, the video can be a useful part of class discussion of censorship and book banning. Though it’s a tempting idea, I would not set up a classroom or school survey to trap students into similar behavior. I want students to think critically about censorship, and I don’t think labeling them as unthinking is a good way to do that.

Instead, I want to play the video for students and ask them what they think is happening. Why are the participants so willing to participate in this book banning activity? I want them to identify how much thought is going into the participants’ decisions and how much peer pressure and the public nature of the survey contribute to participation. I’ll also ask students to look at the setup of the survey. It’s just a simple tick mark on a piece of poster paper. Does that simplicity or the presence of the reporter influence them to participate?

I don’t think the decision to add a vote to the poster is part of some great political agenda, so I will downplay those connections at the beginning of the discussion. When the political aspect of the survey does come up, and I’m sure it will, I’ll ask students to think about how the choice of books and the setting for the survey were part of the reason people were eager to ban the books on the poster. What would happen if the same survey were set up in a conservative town or event?

There are also questions of graphic design to consider: does the layout of book covers on the poster play a part in the response? What would happen if the books are arranged differently on the poster or if the choices were shared only with words (without those very identifiable faces on the book covers)? If the survey itself were presented some other way, would the decision to participate be different?

After all this discussion, I’m thinking of introducing a research project on book banning. Students can research censorship events, like Nazi book burning to more recent censorship of bloggers in countries like China and Egypt. The focus can be widened to include films, songs, and other texts as well. Research questions like these could inspire papers or presentations:

- How does peer pressure contribute to participation in book burnings?

- What other persuasive devices were involved?

- Are there political agendas at play in the choice of what has been banned?

- Does the fact that just one book is banned simplify participation?

- Who decided what was banned? What motives were at play?

- How did people involved respond to censorship?

Supplement your discussion with resources on censorship on the American Library Association website.

If I decide not to go with a research activity, I may stick with the survey itself and ask students to write short responses that they’d give if they were asked, “Which books would you ban?” Answers can be anything from a 140-character Twitter posts to a video response or PowerPoint presentation. The resulting pieces can be part of public service announcement campaign during Banned Books Week.

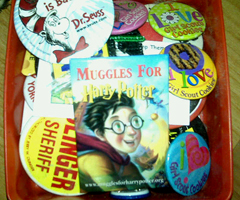

[Photo: polaroid_banned books by karen horton, on Flickr]

One of my cherished possessions is a Muggles for Harry Potter pin from 1999. Eric Crump gave it to me, having picked it up from the NCTE librarian. I hadn’t read a word of J. K. Rowling’s first book, but I was willing to join the anti-censorship campaign.

One of my cherished possessions is a Muggles for Harry Potter pin from 1999. Eric Crump gave it to me, having picked it up from the NCTE librarian. I hadn’t read a word of J. K. Rowling’s first book, but I was willing to join the anti-censorship campaign.