A Year-End Activity with Literary Lists of “Ten Best”

May 10, 2010

There’s not much time left in the school year, and you may find that students are uninterested in reviewing for final exams when they could be making plans for summer fun or a few days off between terms.

There’s not much time left in the school year, and you may find that students are uninterested in reviewing for final exams when they could be making plans for summer fun or a few days off between terms.

You can use the literary lists of “Ten Best” from the UK newspaper The Guardian as the basis of a student-driven exam review activity that can add a bit of fun and entertainment to the last days in the classroom.

If time is short, you can share a relevant list with a class and discuss the examples. Look for a list that fits the content the class has covered, or find one that lists a text that students have read during the course. If students have enough background in the area that list covers, you can discuss whether you’d change the list.

You can also ask students to extend one of the existing lists with something from a reading. Time may require that you narrow the options, so you can give students a list of several options from your readings and ask them to choose one or two to add to one of The Guardian lists. The lists on lotharios, monsters, and unrequited love are focused broadly enough that you’re bound to have read a text with some examples for at least one of the categories. If you’re teaching American literature, the list on American frontier would work well.

If time allows a more in-depth project, have students make their own lists, modeled on the examples from The Guardian:

- Choose several literary lists and share them with the class.

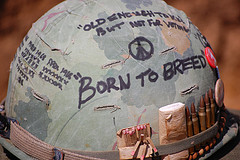

- Ask students to look at the both the things that are listed and the information included for each item on the lists (e.g., short plot summaries, descriptions of the relevant characters, and quotations). You might share the heroes from children’s fiction list and the books about war with students to demonstrate how images can be included.

- Explain that students will make their own lists, using The Guardian lists as models.

- Brainstorm some possible topics for class lists, based on the readings of the term. Encourage creativity. Maybe the class will come up with some options as unique as best tattoos or best pairs of glasses.

- Narrow the list down to the topics that will work best for the class if desired.

- Arrange students in groups. Have each group review the brainstormed options and decide on a topic to explore.

- To ensure that everyone in the group contributes, ask each group member to find 3 to 5 items for the group topic as a homework activity. If desired, narrow the homework further by having each group member search through a different section of the class textbook or a different time period that you’ve covered (e.g., Student 1 takes readings from the 1700s, student 2 takes readings from the 1800s).

- During the next class session, have group members share their suggestions and narrow their collection down to ten items. You might ask students to rank the items or announce that, like the lists from The Guardian, the order has no relevance.

- Have groups add the appropriate details for the items on their list, following the models from The Guardian as a minimum requirement. If desired, groups might make their list more robust by adding images, sound effects, or music.

- Ask students to prepare their lists to share with the class. Depending upon your classroom resources, you can have students read their lists, create overhead transparencies, posters, or Powerpoint presentations.

- Once all the work is completed, have groups share their lists as a review of all you’ve read during the year.

The activity works well because students get lost in the task and forget that they are actively reviewing all their readings for the year. I’ve had students voluntarily reread texts to find evidence when they work on projects like this one.

Customize the activity as appropriate. If ten items seems too long, just adjust the number. “Five Best” would work just as well as ten. The number is fairly arbitrary. There’s nothing magical about the number ten after all.

Add a reflective piece, if you wish, by having students journal about why they have chosen the items they have (and why others have been discarded). While the examples all focus on literature, the activity could be adapted to other content areas. Students can gather the “Ten Best” scientific innovations they’ve learned about during the course, or they can list “Ten Best” historical documents for a history or social studies class.

Encourage more synthesis and analysis by asking students to rank the items on the lists. Groups might narrow their lists to the top three or four items. You can then set up voting that asks students to rank the top items. Take a look at Mother’s Day: 12 Of The Most Horrifying Mothers of Literature from The Huffington Post. Along with the list of moms and their descriptions, the article includes a poll that asks readers to rank the characters. The Huffington Post list may not be one that is appropriate to use in the classroom, but the online poll demonstrates one way you might invite students to vote (and it makes the results easy to tabulate).

Finally, you can tie the activity to the final exam for the course itself with these suggestions:

- Give students a full list and ask them to narrow the list to the 3 or 4 best and to justify their opinions.

- Have students take a list and draw conclusions about how the topic has been defined by your readings. Using an example list from The Guardian, for instance, you might ask, “What are the characteristics of a lothario, based on the characters listed as Ten of the best lotharios in literature?”

- Ask students to transform one of the lists to an “Eleven Best” by adding an item to an existing list. Have them write an explanation of how the item would be appropriate.