June 26, 2005

by Traci Gardner

Perhaps this will interest no one other than me, but I think it’s a reminder of how we sometimes forget who we are and what we know. I struggled for weeks with the text I’m trying to write. I’m still trying to write it, and in many places it is crappy extraordinaire. I’ve just been unable to write anything useful and equally unable to figure out why I can’t write anything. I mean. Look, I’m a writer. It’s what I do. While I was stuck, I was writing lesson plans and Inbox entries and even a conference presentation—but I couldn’t write my manuscript.

I was sitting on the Selfes’ porch last Thursday, writing and rewriting the same damned pages. Gracie was lying nearby, but she wasn’t any help at all. Cindy was even sitting across from me for a while, writing like the writing fiend that she is. There’s something really odd about trying to write when your role model/idol is sitting across from you. But that’s a different entry.

The point was that I couldn’t write, and I had over the course of the weeks blamed a million things. The desk wasn’t comfortable in the apartment, so I rearranged things and even got a lightweight TV-type table to solve that problem. The chair wasn’t comfy, so I bought a folding chair that was better. Still stuck. I rearranged my writing and set up so that I was writing in the comfy stuffed “living room” chair. Still blocked. I tried writing in the CCLI. I tried writing at multiple machines, Mac and Windows, different locations. I still wrote crap or couldn’t write at all.

So here I was on the Selfes’ porch. I had a good chair and a large table. I had writing stuff all around me. I had doggies to pet. I had a great view of woods and wildlife. I was hoping for a moose, but one never showed up. Still, I was stuck writing crap. Okay, it was thickly humid and 90+ degrees and I was dripping like a popsicle in hell; but I knew that the heat wasn’t the problem. I hadn’t been able to write anywhere, after all.

Something about having Cindy sitting across from me made me think about the problem differently. I started quizzing myself. In my make-believe world, I imagined what it would be like if Cindy were to ask me how my writing was going and what I was accomplishing. I knew how to answer that question. My chapters just didn’t feel right. One section was all choppy lists. They read like things that I had written, since parts of them had grown out of Lists of Ten; but they didn’t fit together and try as I might, I couldn’t make them sound not like lists. The Intro sounded something like I would write for an Inbox message. The research section sounded something like a very extended Theory to Practice section from a lesson plan. That or like a self-contained article of its own. Nothing fit together, and none of it felt right.

Now, I realize that I was giving myself a writing conference. Or more accurately, I was making believe that Cindy was giving me one. But it wasn’t solving anything. All I was doing was thinking through the reasons that my text sucks big. Defeated, I started my inner voice of self-hatred and despair. I remember thinking, “You idiot. You’re a writing teacher and you can’t write. What the hell is wrong with you? This is totally wrong and you should be able to fix it. You are writing about writing, damn it. You’re supposed to know how to do this.”

In the middle of this tirade of self-hatred, I suddenly told myself to fucking stop it. The self-hatred wasn’t getting anywhere—but the writing teacher was. Again, I remember thinking, “Okay, you’re a writing teacher. If a student came to you and was this stuck, what would you ask the student to do? You’d tell the student to freewrite. To just journal away about the crap and the problem and whatnot.”

Naturally the evil voice of self-hatred perked back up. “That will accomplish nothing. You’ll waste writing time, and have useless text.” But somehow, I made all the voices just shut up. I shut them down, and I just wrote this:

I want this chapter to explain the basic parts of writing a good assignment. The point is to outline the basic things that a writer needs to do in order to get a good assignment. The tips that are included are all good by themselves, but they aren’t unified and there is no flow to the section. I could try to focus on a single lesson idea as it evolves, essentially writing down the process that I would follow to create the writing assignment itself. Perhaps the best thing is indeed to write a lesson plan and take notes on the process that I follow so that I can show that lesson as a case study of sorts–how it fits together, how the parts flow into one another and into the other parts of the curriculum, and how the piece is assessed.

I think that the problem so far in the text is that it’s all this distant, non-person voice. I mean it’s the voice of the Inbox and whatnot, but that voice isn’t allowed to have an “I” so the text is in some ways w/o its author.

I had to stop prematurely because the ECAC folks were arriving as I was writing the last bit. I didn’t have time to even reread or rethink it. I just hurriedly got the idea down. But the more I did think about it during the ECAC gathering, the more I realized that last idea was it. That was why I was blocked. Those last two sentences finally told me why I was stuck. I had hidden myself and tried to write a text where I didn’t exist. I’ve gotten so used to hiding myself in my Inbox writing, that I was trying to cut myself out of the book—and that’s why I’ve been stuck for 3 weeks. I was trying to silence my voice, and as a result, I couldn’t say anything.

Today, I’ve finally had a chance to go back to the bits that I’ve written over the last weeks, and it’s all so obvious. Every place the text is awkward or convulted, I was trying to write without letting myself into the text. Once I rewrote a bit, allowing myself first-person pronouns and giving myself permission to write about MY experience in addition to the general info and the research. It all works so much better.

I’d like to believe that the breakthrough was being on the Selfes’ porch, sitting across from Cindy. But really, I know that’s not it. The breakthrough came when I started thinking like a writing teacher and applying what I knew to where I was stuck. It wasn’t the desk, the chair, the heat, the books and articles that I did or didn’t have. It wasn’t any of those things. It was that I was trying to write with a voice that wasn’t mine.

Tags: ECAC | writing process

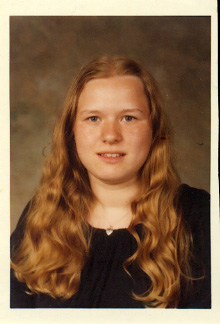

This prompt is inspired by the piece that I wrote about my high school yearbook photo back in August 2009 for Laurie Halse Anderson’s for Write Fifteen Minutes a Day (WFMAD) and that I submitted to Bedford/St. Martin’s Gallery of Writing.

This prompt is inspired by the piece that I wrote about my high school yearbook photo back in August 2009 for Laurie Halse Anderson’s for Write Fifteen Minutes a Day (WFMAD) and that I submitted to Bedford/St. Martin’s Gallery of Writing.