6 News Stories to Connect to Orwell’s 1984

August 31, 2010

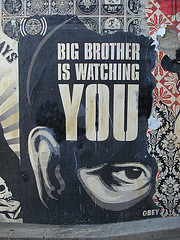

Big brother really is watching you. Today we accept a certain amount of oversight by government and business as a part of daily life.

Big brother really is watching you. Today we accept a certain amount of oversight by government and business as a part of daily life.

Students know about all the surveillance cameras that follow them as they move about in the world. They realize the U.S. government tracks details on their income and health. They know that online vendors know what they buy and everything they looked at before they decide. They have all heard stories of someone who gets a ticket because of an act caught by a traffic light and toll booth camera.

Still, they can bring a skepticism to class when they read George Orwell’s 1984. Seriously, we could never be watched that closely, right?

Several recent news stories may make the answer to that question less certain. Have students read and discuss any one of the stories as an introduction or supplement to 1984, or arrange students in small groups, having each read a different article and then present the information and their comment to the class.

- Someone’s watching Granny cook her eggs. A new video surveillance system watches over senior citizens, monitoring everything from when they get out of bed to whether their eggs are fully cooked.

- Aunt Martha’s been in the bathroom for 30 minutes. Motion sensors track senior citizens around their homes, sending text messages to family when a possible problem arises. RFID chips track medicine and the inventory in kitchen cabinets.

- The scanner says you missed class today. Students must flash an ID card near the university lecture hall entrance to register their class attendance. The resulting information feeds into class participation grades.

- Alert! Preschooler has left the building! Thanks to a radio frequency tag in special basketball jersey-type shirts preschoolers wear, teachers and administrators can quickly tell when a student wanders off campus. The system tracks students at recess, in the cafeteria, and even in the bathroom.

- Why is Will still on the school bus? RFID chips and barcodes on student and faculty IDs and various pieces of equipment will allow a high school to track where people and things are at all times if funding is awarded. If someone’s missing or out of place, they can take action immediately.

- Your recycling bin may tattle on you if you throw away too many plastic bottles or cardboard boxes. In Cleveland, Ohio, RFID chips and barcodes will tell garbage collectors how often you put out the recycling. If it’s not often enough, your trash will be searched and you can be fined $100 if recyclables are found.

Student discussion of the articles can be guided with these questions:

- What freedoms or privacy rights does the system affect?

- What is the benefit of the system?

- How would you feel if you were monitored by the system?

- Would you feel comfortable using the system to monitor someone else?

- How do the benefits balance with the loss of privacy? Is the loss worth the cost?

If students read and discuss several of the articles, additional questions can ask them to compare and synthesize the pieces:

- Notice that the targets of these programs are either students or senior citizens. What do you make of the focus of these systems?

- What other ways are monitoring systems used in America? How do the systems in these articles compare to them?

- Create a scale that outlines how you feel about tracking and monitoring. What should always be monitored? What should never be monitored? What falls in-between? Explain how you decide where to place things on the scale.

Note that these articles would also make a great supplement to M. T. Anderson’s Feed.