Ten Ways to Improve Educational Videos

May 12, 2020

The move to online courses has many of us working to create videos that replace the explanations of concepts and demonstrations of skills that we would customarily do in the campus classroom. The strategies below help make those videos more effective.

The move to online courses has many of us working to create videos that replace the explanations of concepts and demonstrations of skills that we would customarily do in the campus classroom. The strategies below help make those videos more effective.

- Focus

Cover only one topic in your video. Focusing on one topic allows students to hone in on the ideas by lowering the cognitive load. They can take clearer notes and recall the information more effectively. Equally useful, later when a student needs to review a specific concept that is unclear to her, she can quickly find the exact video that addresses that topic. - Keep it short

Effective videos are approximately 6 minutes long (Guo et al., 2014). Longer videos include more information than students can remember. Breaking your course content up into

shorter videos increases students’ ability to comprehend and recall the information. - Forecast

Provide an overview of the point you will cover at the beginning of your video. Your forecast will serve as an advance organizer, telling students what to watch for and providing structure for the video (Ibrahim et al., 2012). - Reinforce

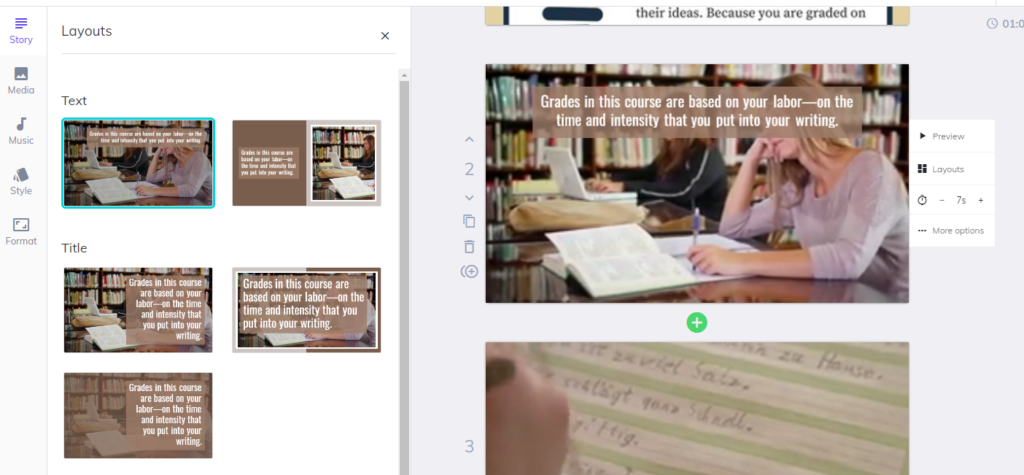

Highlight, or signal, key terms and main ideas in the video by emphasizing them verbally and including the terms on screen (Ibrahim et al., 2012). Place text on the screen near the portion of the image it corresponds with in order to reduce students’ cognitive load (Mayer & Moreno, 2003; Mayer, 2008).

Ideally, the complementary terms and graphics will match those included in your opening forecast (see #3 above), reinforcing the information further. - Limit distractions

“Weeding” irrelevant content out of your videos increases students’ attention and retention (Ibrahim et al., 2012; Mayer, 2008). Extraneous information in videos includes unrelated background music and sounds as well as irrelevant and purely decorative visual elements. - Use basic recording features

You don’t need an entire production team to create effective educational videos. Guo et al. (2014) found that higher production features actually decrease student engagement with videos. Just set up a webcam at your desk for videos, or use screencasting software for demonstrations from your desktop. Focus on what you want to teach students, and forget all the bells and whistles. - Set the stage

Check the background for what students will see in your video. If the video shows a shot of you talking, check what is behind you and remove anything that is unnecessary or unprofessional. If the video shows your computer desktop, remove any irrelevant icons from the desktop and close software that you aren’t using. In particular, be sure that you have no filenames or open files on screen that reveal private information. Taking these steps ensures that students focus on the content, rather than random information in the background. - Add closed captions

Captions help all students, not just those with hearing loss. In a 2014 study, “students commented that the captions made it easier to take notes, improved understanding by watching and reading, helped them learn the spellings of words, enabled them to watch the videos with the sound turned off, and enabled them to follow the videos more closely, as the captions helped focus attention” (Berg et al.). - Name videos specifically

Students will make better use of the videos you record if you choose specific titles and filenames. If your videos are named Lecture 1, Lecture 2, etc., students have no idea of knowing what content they will find. A student trying to find a specific concept won’t know which one to choose. If the videos were instead named plant cell structure and photosynthesis, students would know exactly what each covers. - Provide supporting materials

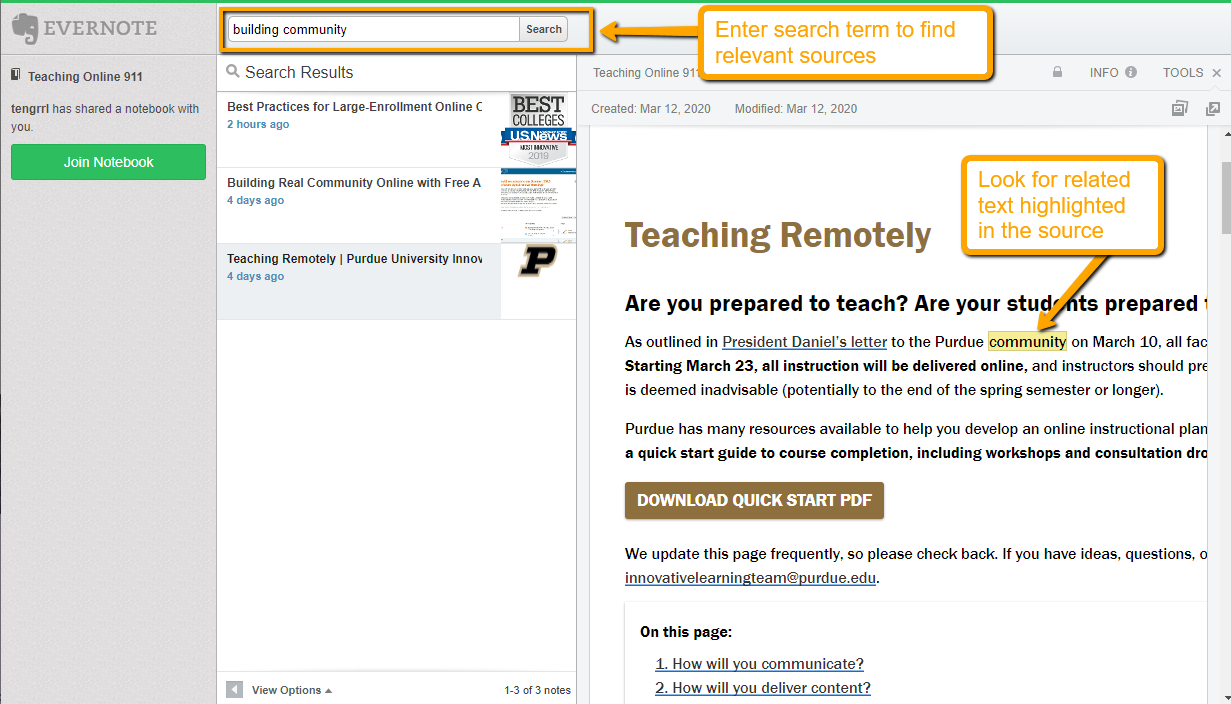

A video alone can help students understand key concepts and learn new skills. A video accompanied by explanatory and descriptive text, related activities, and relevant textbook readings can do even more. Thomson, Bridgstock, and Willems (2014) found that “video is much less effective when it comprises the sum total of the standard lecture/learning experience” (p. 71). Supporting materials, in other words, can make a difference in what students learn and retain.

References

Berg, Richard, Brand, Ann, Grant, Jennifer, Kirk, John S., & Zimmerman, Todd. (2014). Leveraging recorded mini-lectures to increase student learning. Online Classroom, 14(2), 5.

Guo, Philip J., Kim, Juho, & Rubin, Rob (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale Conference — L@S ’14, 41—50. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556325.2566239

Ibrahim, Mohamed, Antonenko, Pavlo D., Greenwood, Carmen M., & Wheeler, Denna. (2012). Effects of segmenting, signalling, and weeding on learning from educational video. Learning, Media and Technology, 37(3), 220—235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2011.585993

Mayer, Richard E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. The American Psychologist, 8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.8.760

Mayer, Richard E., & Moreno, Roxana. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43—52. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_6

Thomson, Andrew, Bridgstock, Ruth, & Willems, Christiaan. (2014). “Teachers flipping out” beyond the online lecture: Maximising the educational potential of video. Journal of Learning Design, 7(3), 67—78. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/jld.v7i3.209

Photo credit: 7 Best HD Webcams in Pakistan for 2019 by Sami Khan on Flickr, used under public domain.

Last Updated on

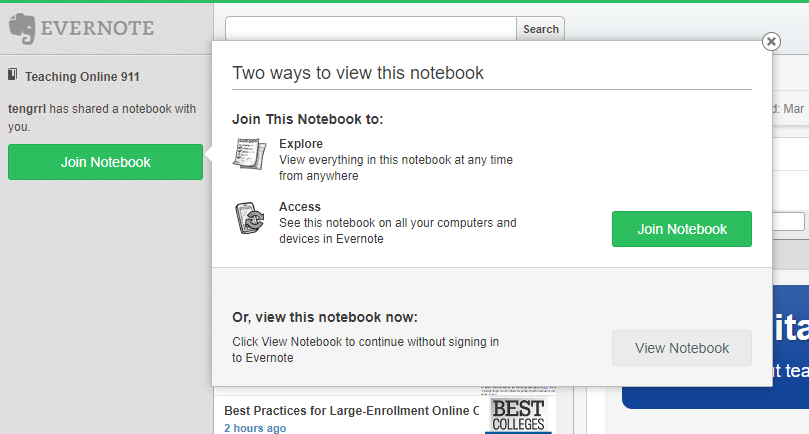

This post originally published on the Teaching Online 911 blog.

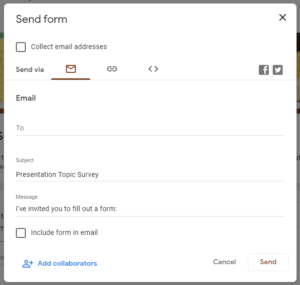

Now that everyone is teaching online, active learning strategies like minute papers and muddiest point are hard to manage spontaneously. In a campus classroom, you can ask everyone to share responses out loud or on a piece of paper. In an asynchronous online class, students aren’t able to participate in quite the same way.

Now that everyone is teaching online, active learning strategies like minute papers and muddiest point are hard to manage spontaneously. In a campus classroom, you can ask everyone to share responses out loud or on a piece of paper. In an asynchronous online class, students aren’t able to participate in quite the same way.

Providing students with instructions on what to do in an emergency is always a good idea. It’s even more important now as all classes are moving online and many students are relying on technology resources more than they are used to.

Providing students with instructions on what to do in an emergency is always a good idea. It’s even more important now as all classes are moving online and many students are relying on technology resources more than they are used to. Problems with vt.edu websites, LinkedIn Learning, or Canvas

Problems with vt.edu websites, LinkedIn Learning, or Canvas