May 5, 2013

by Traci Gardner

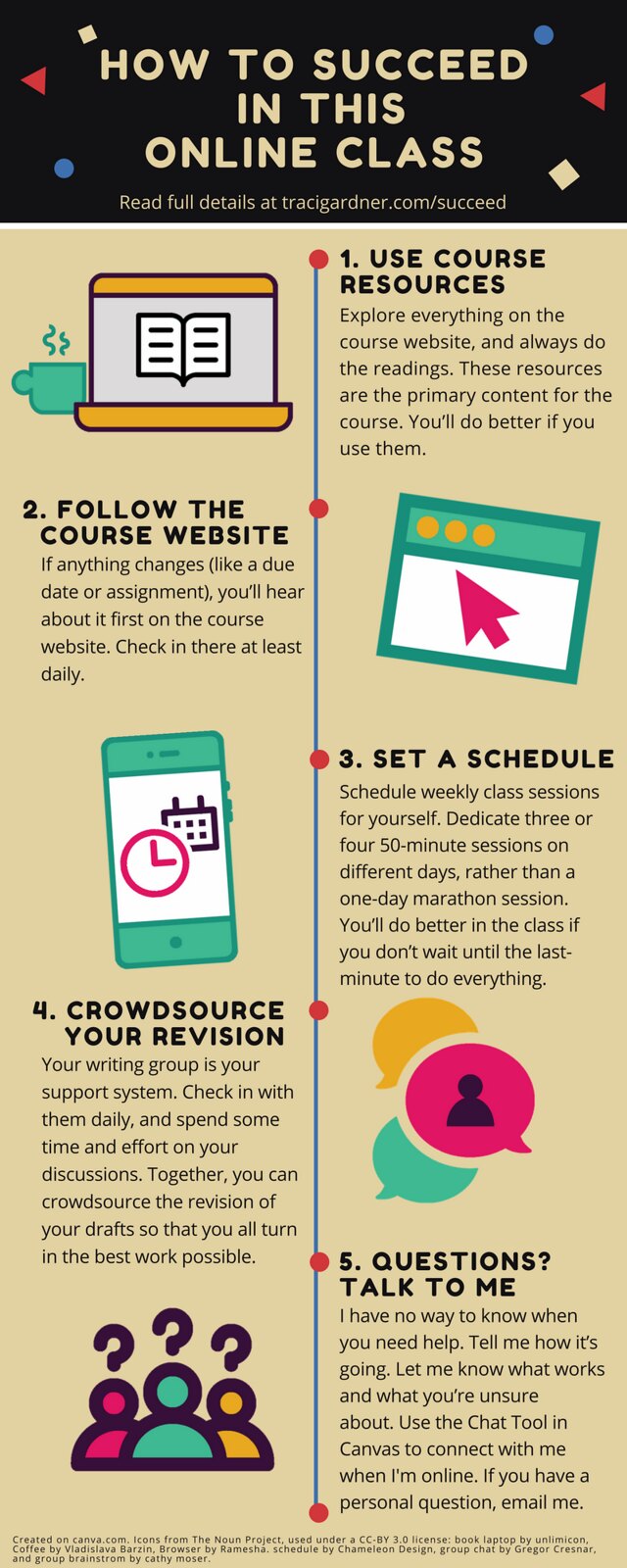

I failed at #WEXMOOC this week. Though admittedly, I feel a little tricked by the nature of the MOOC (defined generally) as well. Our second assignment asked us to reflect on our identities as writers in relationship to three other writers. The assignment gave these instructions:

I failed at #WEXMOOC this week. Though admittedly, I feel a little tricked by the nature of the MOOC (defined generally) as well. Our second assignment asked us to reflect on our identities as writers in relationship to three other writers. The assignment gave these instructions:

[W]rite 800-1000 words where you explore connections between your identity as a writer and other people’s identities as writers. Your audience is other writers in this class.

The assignment seems like the usual stuff of the composition classroom. The audience is quite often other students enrolled in the course. I hadn’t thought through how literally this fact was true however nor how different my audience is in the context of this particular course.

Audience analysis is, of course, my job in a writing project, and I blew it this time. The assignment tells us that we are writing to the “other writers in this class.” Unfortunately, I didn’t think enough about the people who make up WEXMOOC. I imagined the group as somewhere between a typical first-year composition class and what we called a trailing section (that is, students who either took a remediation course or had failed FYC the first time through, so they were off sequence, taking a first semester course during second semester). Some of the students in WEXMOOC are that sort of typical first-year comp student, but there are a lot more international students focusing on Global Englishes than is the norm. Many of the students in WEXMOOC mention other languages that they use. Writing what I think is a good piece or what I believe a typical FYC student would think met expectations fails to connect with these readers. I needed to pitch everything to a global reader and to avoid any moves that did not follow clearly from the assignment. I didn’t think about my audience thoroughly enough to realize that my approach was completely off.

The MOOC is an empty classroom. I can’t see the audience. I do not know them, and because of the huge number of students involved, I probably never will know them. I have to guess at their demographics. I’m not sure where to do research to find out the composition of this particular MOOC. The success of WEXMOOC relies on understanding your readers, but that information is hard to find. I wish the course included more discussion of the audience itself. I would never give an assignment like this without spending time analyzing the audience as a class as well as analyzing several other audiences for comparison. Given that we have limited ability to learn about the members who make up this course, we could benefit from a deeper exploration of this particular audience.

Audience analysis is only part of the problem however. The members of this course need significantly more training in peer review, especially given the structure of this MOOC. Peer review is actually the part of this course that matters. My writing doesn’t need to be what I would call good. It needs to be something that this group of students will peer review as good. Completion in the course relies not just on completing the writing and doing peer reviews, but also on earning a specific average on a 5-point scale from peer readers.

From what I can tell from the two peer responses that I have gotten so far, my readers expected a clear, optimistic conclusion in this assignment. I compared my own background to three others, reflecting with some pessimism on the unfairness of literacy acquisition. It was not an especially brilliant conclusion, but it did follow from what I had discussed. My readers, however, weren’t prepared for anything but an obvious, optimistic conclusion. They wanted me to end with some plan to fix the unfairness that I discussed. They want me to be a better person, not a better writer. One even suggested that I should take some classes in a foreign language so I could relate to the writers I used for my comparison. That is life advice, not how peer review advice. My readers wanted a pretty fable, tied up with a life lesson.

Completion in the course relies entirely on successful peer review. The WEX Training Guide is a good document, but I don’t think it’s enough. It includes only one example review, and that paper was written by a graduate student. That sample isn’t close to the reality of the four papers I gave peer feedback on. Students need more example papers and feedback, including some examples that deal with issues that reflect those students in the course face. An FAQ might even help if it addressed questions like “What if the text doesn’t match the assignment?” , and “Should I mention grammar problems?” As a teacher, I know how to deal with those issues, but I’m not sure that the average student in this MOOC does. Leveling a group of readers for a fair assessment takes time, but when peer feedback matters as it does in this course, you have to take that time.

I opened by mentioning that I feel a little tricked by MOOCs. The pedagogical necessities of MOOCs have created a writing classroom unlike any I have encountered before. This week, WEXMOOC reminded me that the teachers in a MOOC only supervise what is going on. Work is not assessed from a teacher’s perspective, but from the students’ point of view. Writing to peer reviewers is quite different from writing for an objective teacher. Everything relies on those peer reviewers in this course. The size of the course and the range of student writing abilities mean that the staff of a MOOC can never respond adequately to all the writing that students do. If peer reviews matter to the success of a MOOC however, students need more scaffolding to do the work effectively and need a better understanding of one another if they are to meet the expectations of MOOC students as an audience.

[Photo: More empty classroom stuff, UMBC by sidewalk flying, on Flickr]

Ever since I looked at the review of Stuart Selber’s Multiliteracies for a Digital Age in

Ever since I looked at the review of Stuart Selber’s Multiliteracies for a Digital Age in