Public Domain Illustration of Frederick Douglass

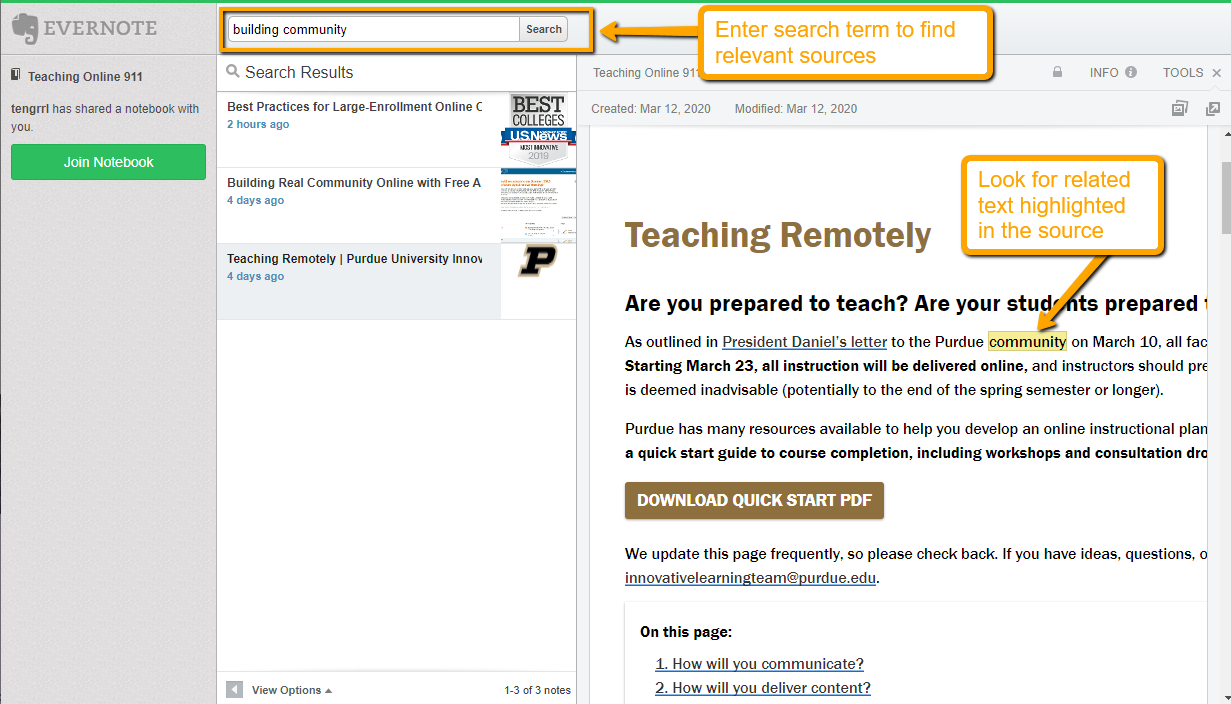

In my last post, I shared details on Encouraging the Use of Public Domain Assets in student projects. Public domain images, video, text, and audio provide free-to-use, copyright-free resources that students can incorporate in any of their work, such as illustrating a pamphlet, creating a slideshow, or producing a video.

The public domain illustration of Frederick Douglass on the right, for instance, could be used in a student project, with details on its source in the Flickr collection of the Internet Archive Book Images as well as the illustration’s original source.

The challenge with public domain resources is knowing where to find them–and that’s my topic this week. I will share several subject-specific sites, and then I conclude with collections that cover a variety of topics. The sites I am sharing do include some video and audio resources, but the majority focus on images.

Public Domain Search Sites and Collections

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

As I mentioned last week, NASA is the ideal source for any student working on aviation, aeronautics, or space-related topics. The NASA website includes three different kinds of multimedia:

Because NASA is a government agency, all of NASA’s multimedia are usable within public domain permissions.

National Park Service

Students can find resources on historical locations, natural landscapes, and the inhabitants of those landscapes. The National Park Service, Multimedia Search can help students find such resources as photos of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial and a video on Preserving the Historic Orchards at Manzanar National Historic Site (a WWII Japanese Internment Camp). The site includes photos, videos, audio, and webcam footage. Do remind students to check usage rights as they decide on resources to use. Most of the materials are in the public domain, but there are some exceptions.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

The USDA Agricultural Research Service maintains an Image Gallery Search that includes photos related to subjects such as crops, animals, food, insects, and lab research. The USDA Agricultural Research site also includes a collection of videos, issued from 1996 to present. The videos focus on various research and news stories, such as this video of Honey Bees Tossing Out Varroa Mites.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The collections in the NOAA Photo Library include all the images from the National Weather Service, highlighting both storm photos and unusual meteorological phenomena. The library also includes collections on Fisheries, Gulf of Mexico Marine Debris, and national marine sanctuaries.

Flickr Resources

Many governmental agencies have collections on Flickr, and you can quickly find them by visiting the USA.gov Group Photostream. The group combines the photostreams of official U.S. federal, state, and local governments on Flickr, with collections from groups ranging from the U.S. Corps of Engineers to the Peace Corps.

The Commons on Flickr is an international group of cultural institutions that provide public domain images, such as the Smithsonian Institution on Flickr and the British Library on Flickr. The group includes museums, historical societies, religious archives, and university collections.

Wikipedia Public Domain Resources

Wikipedia uses public domain images on many of the entries on the site. As a result, Wikipedia maintains a list of Public domain image resources. The dozens of sites listed repeat some of the resources above (such as the British Library on Flickr), but they also include sites that organize images from other collections. While the sites above are all reputable and reliable, the sites on the Wikipedia page may not be. If you recommend this page to students, spend some time talking about how to evaluate Internet resources.

Final Thoughts

In addition to knowing where to find public domain resources, students need to know how to cite the resources they include in their projects. I talk about documentation before students even begin their search for assets to help ensure they avoid citation errors. To my way of thinking, reminding students to gather citation details for a photo is just like reminding them to write down the page number for a book quotation they plan to use.

This week’s links favor photos and illustrations that can contribute to any multimedia project. There are times when students will want to go beyond still images however, so I will share collections that focus on video footage in my next post. Until then, let me know if these sites are useful or share some of your own favorite public domain sources. Just leave me a comment below. I can’t wait to hear from you.

Image credit: Illustration of Frederick Douglass from Internet Archive Book Images, used under public domain.

This post originally published on the Bedford Bits blog.