Literary Lists of “Ten Best”

May 8, 2010

The UK newspaper The Guardian has an ongoing series that focuses on “The 10 Best of” a variety of topics. They’ve covered a range of interests, including fashion, movies, comedy, politics, and music. Fortunately for those of us who teach literature, The Guardian feature has included these unusual literary lists of ten:

The UK newspaper The Guardian has an ongoing series that focuses on “The 10 Best of” a variety of topics. They’ve covered a range of interests, including fashion, movies, comedy, politics, and music. Fortunately for those of us who teach literature, The Guardian feature has included these unusual literary lists of ten:

- Ten of the best elections in literature (2010-05-08)

- Ten of the best visions of Heaven in literature (2010-05-01)

- The 10 best books about being stranded (2010-04-24)

- Ten of the best lotharios in literature (2010-04-10)

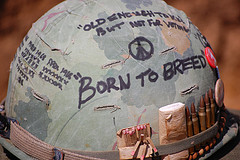

- The 10 best… books about war (2010-03-14)

- 10 of the best: heroes from children’s fiction (2010-03-12)

- Ten of the best monsters in literature (2010-02-21)

- Ten of the best horrid children in literature (2010-02-06)

- Ten of the best pairs of glasses in literature (2010-01-29)

- Ten of the best tattoos in literature (2009-09-26)

- Top 10 tales of the American frontier (2009-07-08)

- Ten of the best examples of unrequited love (2009-03-21)

You’ll find that some of the lists are stronger than others. For instance, I was disappointed to find that the heroes from children’s fiction focused solely on white heroes, and the books about war failed to include Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. How could a list of best war books not include The Things They Carried?!

What the lists do extremely well however is demonstrate a great amount of creativity in topics. That’s certainly the only list of best pairs of glasses or best tattoos I’ve ever seen. Sometimes the lists are particularly relevant to current events, such as the best elections list published today. If you do nothing more than read through the lists, you’re bound to find a new text to add to your reading list—or a reminder of a text that would be enjoyable to revisit.

Come back tomorrow for a great year-end activity inspired by these literary lists!